Finding inner peace in a violent warzone

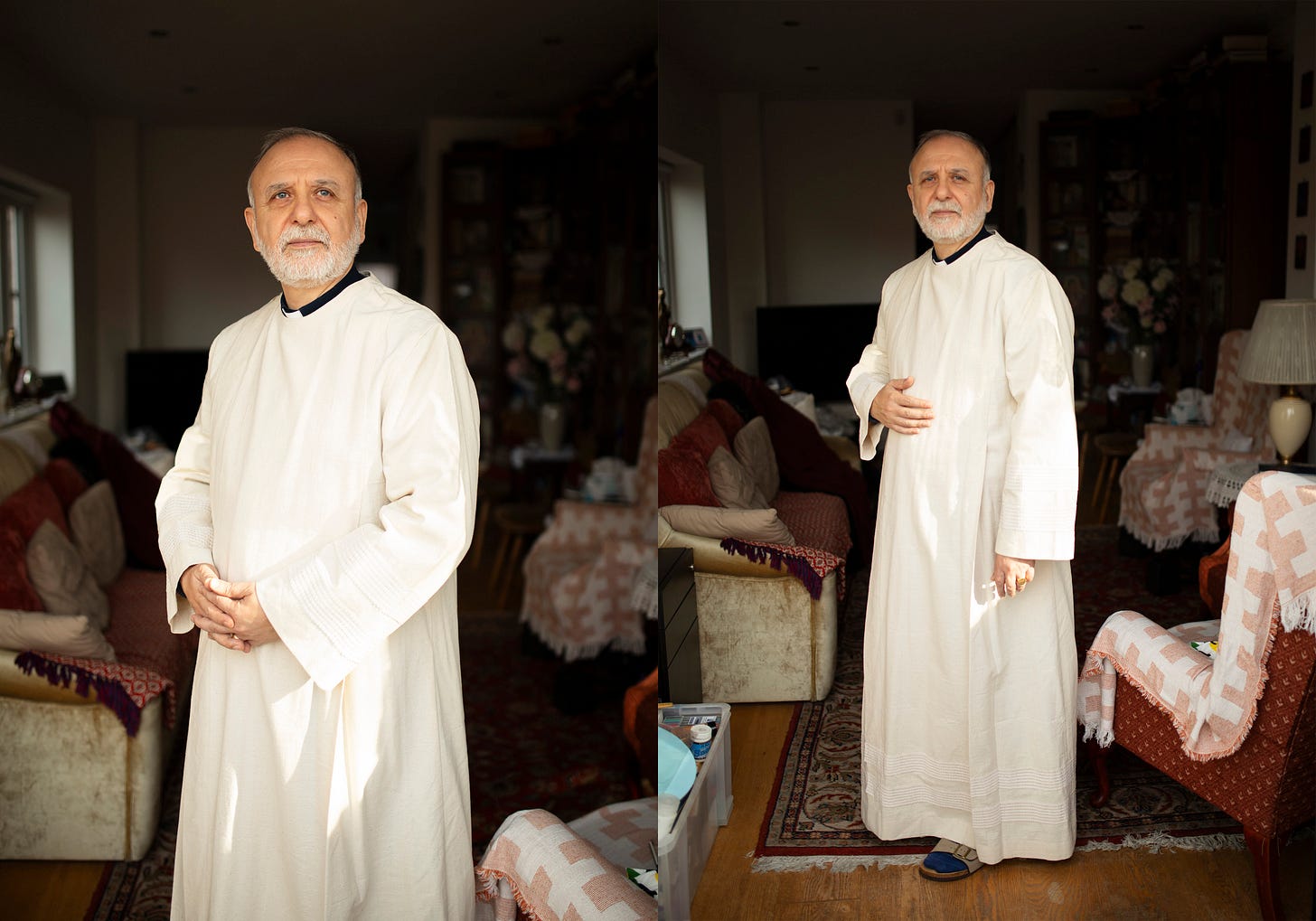

Piecing things together with Rev'd Nadim Nassar: priest, firebrand, and director of the Awareness Foundation.

10 min read | This post is adapted from the final issue of Passio Magazine: our limited print edition which came out twice a year. You can order a copy, and most back-issues, in our shop.

How does it feel to be young and seemingly powerless in a country whose future is being gambled on by distant superpowers, brawling over the oil beneath your feet? A country governed by corruption from bottom to top: from the petty actions of police right up to the 50-year-old dictatorship looming over everything?

It’s the plight of Syrian youth that Nadim Nassar, born and raised in Lattakia, had in mind when he founded the Awareness Foundation and its flagship programmes: Ambassadors for Peace, and Little Heroes. Nadim originally left Syria to study in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War, before moving to the UK and becoming a priest in the Church of England.

When we speak, the overthrow of Assad’s regime in Syria is still fairly fresh news; we squeeze in our meeting before Nadim is due to travel home, to immerse himself in everything that’s going on.

The wall behind him showcases an array of iconography — he explains he has a love for the sacramental side of faith — and a bookcase beside us bulges with theology, history, languages, trinkets and instruments. We’re joined by Nadim’s sister, Huda Nassar: a scholar, polyglot and the Director of the Foundation; she also informs me that she’s learning the piano. It’s fair to say that both siblings are formidable figures, who would be intimidating if they didn’t wear it so lightly: rather, they make me welcome in the house, introduce me to their mother and insist that we stay to eat with them. It’s almost outmoded to say it, but the word that comes to mind is humility.

We’re in the suburban belt that purports to be London but isn’t really London any more; Nadim and Huda had maintained an office in the centre of the capital for a while, but cut loose after the pandemic and haven’t looked back. They work here, instead, in their house, a warm but innocuous enough space; you certainly wouldn’t guess at the deep network of roots that spread from this terraced house, out across Europe and deep into the Levant.

Now over 20 years strong, the Awareness Foundation is, at heart, a force for peace in the world, specifically in the Middle East. Its core programmes aim to teach skills, and give tools, to children in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon: spiritual and practical skills that help them to regain hope, and build better futures for both themselves and their families.

The centrepiece of that training, as Nadim explains it, is “the art of dialogue — because in Syria, that has been forbidden. Children, young people; they had to be obedient. No questioning. No opinion.”

We are talking about the “brutal” Assad regime, the backdrop to the Foundation’s birth in 2003: “We have, I don’t know, 30 different departments of secret police? The regime lived in a paranoia. They never worked out that maybe serving the people is the best way to stay… maybe to offer them a good life? It never occurred to them.”

The Foundation, then, was born on the back of a political tumult which cannot really be said to have died down in the two decades since: back then, Bashar al-Assad’s regime had just begun, and would soon take its shape as one of the most repressive regimes of modern times—even worse than his father’s reign before him. The seeds were being sown, too, of the horrific civil war that would engulf the country after the Arab Spring.

One way to put it is that Syria has suffered from the same curses that befall any nation that happens to be resource-rich. “Peace becomes difficult when a country has a lot of resources,” Nadim puts it. “Because the cake is very appealing to many foreign powers, and they want to divide the cake. For us, we have Russia, Iran, Turkey, US, UK, Europe — as long as there is no decision on how to divide the cake, there is no peace. It’s a proxy war. Assad sided with the Russians—but what now? We’re going to find out.”

On Assad’s fall, Nadim brings a wisened edge: this only happened because Putin abandoned the regime, he says frankly, but he is winsomely proud of the responsiveness and creativity of their young Ambassadors group in the wake of these huge events. The young people created a network on the ground, sharing information and helping each other to stay safe, while soldiers abandoned their posts and almost all assumptions were up in the air. Since the new transitional government has been in place, the Ambassadors have been igniting discussions on the future of Syria: showing an abundance of imagination and ideas in this remarkable, liminal moment.

Nadim’s cautious about where this all goes next. “It’s early. The provisional president is, ultimately, imposed on us,” he says cautiously. “What he is promising is very good: but there are a lot of question marks, and fears. An Islamic radical constitution doesn’t work in Syria; because Syria is a mosaic, and every piece of this mosaic is valuable. We have to understand that.

“But we live in a jungle now, in Syria,” he continues. “There is no police, no army. There is a government who are intoxicated with victory, and believe they have the power now. Some are already abusing the power; some of them are calling to stop it.” Amongst it all, his concern for, and his pride in, the Ambassadors for Peace is palpable: “Those young people are heroes—heroes to us,” he stresses.

When you get a glimpse of what young people in Syria have been living through, you understand the ardour and warmth in Nadim’s words.

“I don’t believe there’s a family in Syria that did not have a victim of the Assad regime,” he says. “We all had suffering. But the young people in Syria are going through hell. They need guidance, a compass.” The Foundation gives these young people the opportunity to find that direction through deepening their faith, discovering a real, individual connection with the divine that can give them strength. “It’s only when you find Christ as a compass inside you, that leads, points you always to God, that you start to find your inner peace.”

There’s an undeniable gravitas to the man as he speaks about inner peace. The quiet and warmth of this suburban house feels incongruous with his descriptions of war-torn cities, yet it’s not hard to recognise the embattled self-assurance in Nadim: clear-minded, plain spoken and possessed with a ready confidence. It’s not the forced confidence of a politician or executive, over-eager to assert themselves: it’s something very different.

It’s a peace that, he tells me, he found the hard way, while studying in Beirut in the 1980s. “I lived there for 7 years during the height of the civil war. It was the craziest city in the world at that time: shelling, shooting, explosions everywhere. I could have died any minute: there were five or six times where I was just about to be killed. I couldn’t find any inner peace at first: the noise is too much. It’s not easy at all.”

As much as I push the question, I feel aware that discovering your inner peace in a warzone might not be the easiest process to describe to me—it is, I sense, deeply personal, and borne out of suffering that can’t be neatly packaged. “The more you encounter violence, bloodshed, corruption; the more your faith pushes you towards a mystical element, in order to derive power from it, to sustain you. In this chaos around you, you need an oasis of spirituality, of peace, from inside.” Without this, he adds emphatically, it’s impossible to create peace on the outside: “Unless you are in touch with your inner peace, you don’t have the tools to be a peacemaker.”

“The more you encounter violence, bloodshed, corruption; the more your faith pushes you towards a mystical element, in order to derive power from it, to sustain you.”

It’s that inner peace, then, that the Foundation are trying to give to their young people—starting with that art of dialogue. “We create a safe space; help them to be free in that space, free to speak, to discuss, to pray, to express their fears. Space to cry without shame, and to express their doubts about God. You train them to be themselves. And what they share is so profound.”

Often, the Foundation had to get creative with their terminology to escape the eyes of the regime. “We don’t talk about democracy: we introduced ‘the theology of opinion’. We trained young people to respect their own opinion. We taught them to respect their choices, no matter how limited they are.”

They may have avoided the term for political reasons, but I realise this actually goes deeper: “Our choices are not to be taken lightly, but not because of democracy,” Nadim enthuses. “Not because of human value. The image of God that we are created in, requires us to respect our opinion. Christ gave us the respect for how God has created us. That really resonated with the young people. They never believed their opinions mattered, or had any value.”

Creating space, for young people whose lives have been shaped by fear and political oppression, provides the first key to finding an inner peace, but is not the end of the process. “It’s the most difficult thing,” Nadim affirms. “The threats are enormous outside. It’s lawless. It’s war, so everything [bad] is available. We have to guide them away from that, and still help them to find meaning for their existence, inside the war. It’s difficult, but it’s the most profound exercise you can ever have. I’m stunned by the power of the Holy Spirit, transforming their lives and empowering them to become his peace agents in their broken communities.”

During his life in the West, Nadim has sometimes been made into a figurehead for the presence of Christianity in the Middle East. He has a well-worn anecdote on the way Westerners will assume he is a recent convert to Christianity, or that his parents were: and he has to remind his listeners that modern-day Syria is, in fact, the birthplace of the Christian movement—that the Middle East is “that region of the world that God chose to live in when he took human form”. Damascus, of course, is still sitting there: the oldest inhabited capital in the world.

“The Levant is the birthplace of all three Abrahamic faiths; the people are very passionate, driven by their hearts. People are religious; and over-religious,” he explains, but he’s equally convinced that the religiosity is often skin deep: a morass of religion-as-culture which is bearing bitter fruit. “I promise you, the most aggressive atheistic current in the world, at the moment, is in the Middle East. In Egypt, Iraq, Syria, even in Lebanon. Go inside Iran and see how the people live: they are obedient to Islam by force, not by love. And Iran is an ‘Islamic nation’—well, what does that mean?”

This is familiar territory for the West: the roots of the widespread disenchantment with religious institutions surely go deep into the many, many years where the church took people’s fealty for granted. “I always say to Syrians, learn from the history of Europe. Islam is acting now like the church acted in the Middle Ages: they just want the power. When the church did this, in the European religious wars, it was awful: some of their bloodiest chapters of history. The Kings and Princes were in bed with the clergy, and it was the political institution that abused the Christian institution. It led us where we are today.”

It reminds me of the way calls for a ‘Christian nation’ have become not much more than a right-wing dog-whistle, I say. “I don’t believe in a religious nation. Our relationship with God is not collective; it is individual. It is your relationship with God, and when we come together, we become the body of Christ. Imposing religion is not what God wants. Any so-called ‘religious nation’ can only be an abuse of religion for economic gain.” In those terms, where does he see the church in England now?

“The establishment church is still playing games for me. It is a flirting between the political institution and the religious institution. I don’t like it at all. There is no sustainable argument for us to still be in bed with politics. For the Prime Minister to be involved in the appointment of the Archbishop. Was this the position of Christ to power? How can you challenge power when you are expected to support it? The political power loves this entanglement; they say ‘it’s great that the church cannot challenge me! Keep close!’”

“I don’t believe in a religious nation. Our relationship with God is individual; when we come together, we become the body of Christ.”

Nadim, for one, would’ve been likely to oppose the British Government’s action in Syria, in 2018. Instead, he had to watch his Archbishop sanctioning the bombing of his country, by invoking the controversial ‘Just War’ theory—which may have had the edges sanded off nowadays, but is also understood as the cornerstone of the Crusades and other atrocities. A BBC journalist, interviewing Nadim, was briefly blindsided by the revelation that Justin Welby had not, in fact, spoken to Nadim—the only Syrian priest in the Church of England—before this statement.

“I felt awful, of course,” he says now. “He invoked one of the most controversial theories in the church, in order to support the government. Is this the church we want? Where is the prophetic voice?”

It seems unlikely, I say, to expect the challenge to power to come from the ‘top’. Were the church to push the difficult questions—about the UK’s annual billions in arms sales, for example, the majority of which are sold to countries with poor human rights records—it seems likely that the government would finally cut them loose, no? “Well, that’s what I would like to see!” he smiles.

“The English hide behind something called tradition. Nobody respects tradition more than I do. But I do not accept the tradition to be a chain around my neck. I am only obedient to the tradition of Christ. Jesus was revolutionary; he broke barriers. When he spoke to the Samaritan woman at the well, he didn’t think ‘oh, the enmity goes back centuries, I have to abide by the tradition’.”

I think I can see that Nadim does, indeed, respect tradition, and the institution; probably more than I do, and I don’t say that pejoratively. Yet my conversation with him gives me the hopeful reminder that ‘the Church’ is far more than our institutions. The ‘system’ we see and critique is one small face of it, and perhaps one day the Anglican church will, in fact, be disbanded, whether for challenging power or for something less satisfying. But I want to believe that the Church has always really been individuals, sitting across from each other, bringing their immeasurably different cultures and experiences to one same table, because of the guidance of that inner compass.

Some individuals may have got there through the institution. Some individuals may have followed the compass without knowing the name on it. That’s how I want to think about the church: that it’s made of individuals like Nadim, and also the young people of incredible bravery and resolve that he meets and carries with him. We are each running from different things, but the face of Jesus, the glimmer of real peace, pulls us all, eventually, in the same direction.

You can support the work of Awareness Foundation here. Pick up a copy of Passio Magazine Issue 15 here while stocks last.