Seeds of Wisdom

Community gardener and Uni chaplain Samuel Ewell shares what plants have to teach us about the economy of gifts.

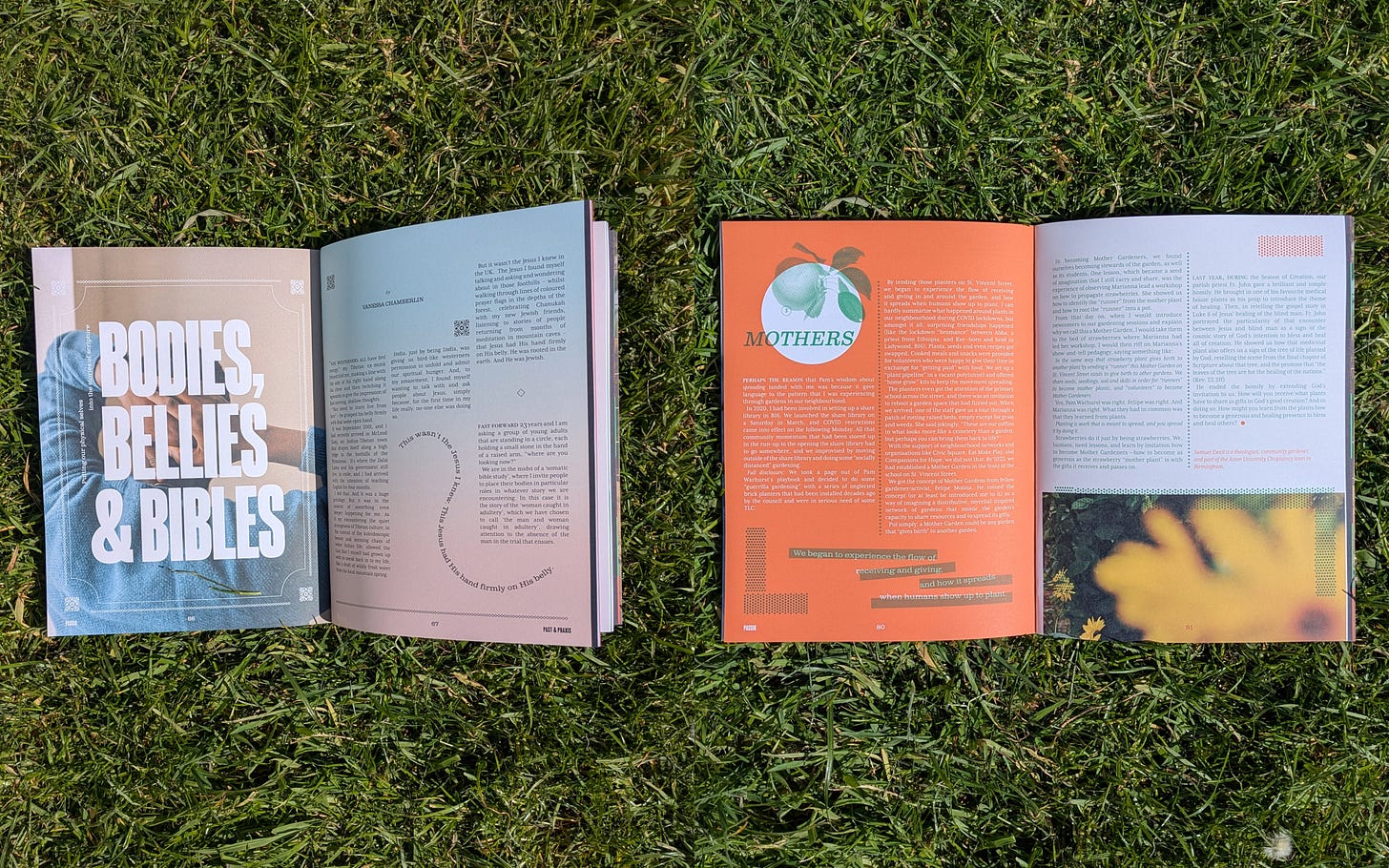

10 min read | This post is adapted from Samuel Ewell’s excellent Substack, Desiring Life; this edited version appeared in the final issue of Passio Magazine — which you can still pick up in our shop. Our back-issues are sold out, but available as PDFs.

I am fascinated by the way that the activity of planting is intimately related to what we might call a “gift economy” — by which I mean all the ways that we receive and share gifts that do not come with a price tag (eg., food, clothing, shelter, artefacts, time, music, experience, presence), and therefore, in which money is not the measure of value.

Whether it’s saving or sowing seeds, transplanting seedlings into a raised bed or exchanging them at our neighbourhood plant/seed swaps, I have come to see that the way I access and handle plants and seeds disposes me to perceive their giftedness — a kind a treasure that is received in order to be shared, not made by human hands, nor earned to be hoarded.

This pattern of gift that permeates the garden has much to teach about the patterns of receiving and giving in our social relationships, as well. My friend Dougald Hine asked it this way: What seeds are you carrying with you? He posed this question in the context of a learning journey called Regrowing a Living Culture. As he guided us on this journey, he shared stories, wisdom, questions, and experiences that he had received as gifts that had seeded his own imagination. As he sowed them throughout the course, he also invited us to consider what seeds had been sown into our own lives.

In calling them seeds, Dougald was nudging us first to notice, and then to have the courage to share, the gifts that we had received. After all, history shows that—both in the fields of ideas, and in the gardens we tend—humans are the consummate seed-spreaders. At our best, we have learned that seeds are only saved and stored in order to be sown.

As Robin Wall Kimmerer puts it in Braiding Sweetgrass, “[g]ifts from the earth, or from each other, establish a particular relationship, an obligation of sorts to give, to receive, and to reciprocate.” In fact, in Braiding Sweetgrass I hear a contemporary echo of ancient biblical wisdom passed down by St. Paul: What do you have that you have not received? And if you received it, why do you boast as if it were not a gift? (1 Cor. 4:7)

What seeds are you carrying with you? When I first heard it, that question really landed with me. It gave me permission to pause and take stock of my ‘seed library.’ It also gave me permission to cultivate the desire to sow these seeds as generously as they had been sown into my life. So, here are a few garden-related seeds that I would like to share with you.

Back in 2007, I encountered a friend in Brazil who was turning his balcony into a productive vertical garden. His solution was as simple as it was profound — instead of throwing away his food waste, he composted them in a wormery to make soil, and grow food. While I was fascinated by his description of how his fifth-floor garden worked, what impressed me most were the reasons he was doing this. Claudio explained that his little balcony garden was an experiment in finding ways to treat creation as creation, and not as rubbish; for honoring the Creator as Creator, and for offering signs of hope and life amid so much urban waste.

When I mentioned wanting to do this from my fourth-floor balcony, instead of giving me a pep talk, he gave me a warning instead:

“Sam, of course, you can compost your food scraps from your balcony, and you should. But I have to warn you that if you do, it may be the most subversive thing that you can do inside your home.”

I must have look perplexed, so he did a little show-and-tell exercise by picking up a decomposing banana peel out of his wormery to make the point:

“In our tradition, we are told by our ancestors that in the beginning, God created and said, ‘It is good.’ This banana peel that I am holding is good. When God sees it, God says , ‘It is good.’ And if God says, ‘It is good,’ then who gave us the right to call it rubbish [or lixo, in Portuguese]. By whose authority do we get to call this banana peel lixo and treat it like lixo?”

Of course, I had no direct answer for that question, and I am still haunted by it nearly 20 years later.

To break the awkward silence, Claudio began to answer his own question : “The truth is we are not authorized to treat it like lixo. And if you begin to handle your own food scraps—like this banana peel—as creation, then it will never be lixo again. You will see it as creation, and you will rethink what lixo is and what we are called to do with creation.”

Claudio’s parting shot: “Então, mano… composting food scraps is subversive because it is about learning to repent and rethink how we treat God’s good creation.”

That was the “coin drop” moment for me. It was a kind of unveiling that exploded my previous conception of ecological activism; no longer was activism fundamentally about doing to or even for the environment, but about working with the divine patterns woven into creation.

When Claudio held up that banana peel and spoke his testimony, that banana peel became a microcosm of the whole creation. Somehow, I saw the whole world in that banana peel. At this point I had already studied biology at university, and then gone to a graduate degree in theology. I had acquired a lot of info and “book knowledge” about both topics. And I probably recycled as best I could. What changed and converted me in that moment was not more information or killer stats, but the presence of the truth that God does not do waste.

“This was the coin drop moment: no longer was activism about ‘doing to’ or ‘for’ the environment, but about working with the divine patterns woven into creation.”

One seed of wisdom that I find myself sharing frequently is a word that was spoken by community food activist, Pam Warhurst. Pam is most widely known as one of the founders of Incredible Edible, a network whose vision is “to create kind, confident and connected communities through the power of food.”

Pam spoke at our annual neighbourhood summer festival and told the story of how Incredible Edible began when residents in the market town of Todmorden came together to care for a derelict green patch of a public square. Technically, they “guerrilla-gardened” it, which means that they cultivated it without formal permission. Turns out the gamble paid off, as more guerrilla-gardening and formally permitted planting ended up spreading like a rumour.

At the time that Pam gave her talk back in 2022, there were around 150 Incredible Edible projects scattered across the UK and beyond. (And those are just the officially registered ones). When she finished here whistle-stop tour of Incredible Edible-land and the Q & A began, the first question was:

“Pam, this is so inspiring, but the scale of the problems with the broken global food system is so vast, how do we scale up the alternatives that you describe?”

You could hear a pin drop, and without missing a beat, Pam responded:

“You don’t. You don’t scale community-led food initiatives, you spread them. And you spread by doing them.”

Pam is the best kind of evangelist with a contagiously inspiring energy about her. Listening to Pam get ‘evangelical’ about the power of food, there was a felt-sense that you were listening to someone who had spent time learning from plants about the power of spreading what is good, true, and beautiful.

I remember thinking if there had been an “altar call” that day, I would have gone forward to rededicate my life to the work of sowing seeds like that one we received that day from Pam.

Perhaps the reason that Pam’s wisdom about spreading landed with me was because it gave language to the pattern that I was experiencing through gardens in our neighbourhood.

In 2020, I had been involved in setting up a share library in B16. We launched the share library on a Saturday in March, and COVID restrictions came into effect on the following Monday. All that community momentum that had been stored up in the run-up to the opening the share library had to go somewhere, and we improvised by moving outside of the share library and doing some “socially distanced” gardening.

Full disclosure: We took a page out of Pam Warhurst’s playbook and decided to do some “guerrilla gardening” with a series of neglected brick planters that had been installed decades ago by the council and were in serious need of some TLC.

By tending those planters on St. Vincent Street, we began to experience the flow of receiving and giving in and around the garden, and how it spreads when humans show up to plant. I can hardly summarise what happened around plants in our neighbourhood during COVID lockdowns, but amongst it all, surprising friendships happened (like the lockdown “bromance” between Abba, a priest from Ethiopia, and Ray—born and bred in Ladywood, B16). Plants, seeds and even recipes got swapped. Cooked meals and snacks were provided for volunteers who were happy to give their time in exchange for “getting paid” with food. We set up a “plant pipeline” in a vacant polytunnel and offered “home grow” kits to keep the movement spreading.

“We began to experience the flow of receiving and giving, and how it spreads when humans show up to plant.”

The planters even got the attention of the primary school across the street, and there was an invitation to reboot a garden space that had fizzled out. When we arrived, one of the staff gave us a tour through a patch of rotting raised beds, empty except for grass and weeds. She said jokingly, “These are our coffins in what looks more like a cemetery than a garden, but perhaps you can bring them back to life?”

With the support of neighbourhood networks and organisations like Civic Square, Eat Make Play, and Companions for Hope, we did just that. By 2022, we had established a Mother Garden in the front of the school on St. Vincent Street.

We got the concept of Mother Gardens from fellow gardener/activist, Felipe Molina. He coined the concept (or at least he introduced me to it) as a way of imagining a distributive, mycelial-inspired network of gardens that mimic the garden’s capacity to share resources and to spread its gifts.

Put simply: a Mother Garden could be any garden that “gives birth” to another garden.

In becoming Mother Gardeners, we found ourselves becoming stewards of the garden, as well as its students. One lesson, which became a seed of imagination that I still carry and share, was the experience of observing Marianna lead a workshop on how to propagate strawberries. She showed us how to identify the “runner” from the mother plant and how to root the “runner” into a pot.

From that day on, when I would introduce newcomers to our gardening sessions and explain why we call this a Mother Garden, I would take them to the bed of strawberries where Marianna had led her workshop. I would then riff on Marianna’s show-and-tell pedagogy, saying something like:

In the same way that strawberry plant gives birth to another plant by sending a “runner” this Mother Garden on St. Vincent Street exists to give birth to other gardens. We share seeds, seedlings, soil and skills in order for “runners” to become mother plants, and “volunteers” to become Mother Gardeners.

Yes, Pam Warhurst was right. Felipe was right. And Marianna was right. What they had in common was that they learned from plants.

Planting is work that is meant to spread, and you spread it by doing it.

Strawberries do it just by being strawberries. We, humans, need lessons, and learn by imitation how to become Mother Gardeners —how to become as generous as the strawberry “mother plant” is with the gifts it receives and passes on.

Last year, during the Season of Creation, our parish priest Fr. John gave a brilliant and simple homily. He brought in one of his favourite medical house plants as his prop to introduce the theme of healing. Then, in retelling the gospel story in Luke 6 of Jesus’ healing of the blind man, Fr. John portrayed the particularity of that encounter between Jesus and blind man as a sign of the cosmic story of God’s intention to bless and heal all of creation. He showed us how that medicinal plant also offers us a sign of the tree of life planted by God, retelling the scene from the final chapter of Scripture about that tree, and the promise that “the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.” (Rev. 22:2ff).

He ended the homily by extending God’s invitation to us: How will you receive what plants have to share as gifts in God’s good creation? And in doing so: How might you learn from the plants how to become a generous and healing presence to bless and heal others?

Samuel Ewell is a theologian, community gardener, and part of the Aston University Chaplaincy team in Birmingham.

☝️ Get the last few print edition copies of Passio in our shop.