The Gospel of Dignity: Van Gogh's Black Boots

Vanessa Chamberlin describes finding the 'Gospel', the good news, in the fight for dignity and care.

Today’s post comes courtesy of guest writer Vanessa Chamberlin, who creates deeply thoughtful work over at the Tuning Fork, which is well worth your time. Vanessa also featured in the final issue of Passio Magazine — last copies only available until the end of the year!

I have been asked to join a panel next weekend, where young people from around the world get to ask whatever questions they like about the Bible.

I felt okay about it, until I was sent examples of the questions they might ask, most of which were, unsurprisingly I guess, around doctrine, rather than story or lived experience. And the first made me want to bolt: “What is the Gospel?”

I don’t have answers for these kinds of questions any more. And when faced with them, I’m as curious as anyone as to what words will fall out of my mouth. I’ve been told that’s why they’ve asked me to be on the panel. They know I’ll bring an embodied, experiential perspective that will likely open up, rather than answer, their questions.

But what does ‘The Gospel’ mean to me now? And how is it good news?

The last time I was asked about this, I shared this image. Van Gogh’s ‘Black Boots’ of 1886 (it’s actually been given the title Shoes, but I prefer my title).

Before sharing its relevance (for me) to the gospel, I asked the young people to tell me what they saw. “A pair of old, worn black boots.” “They belong to someone doing manual labour I think, or working in the fields.” “They are a symbol of poverty and labour… they only have this one pair of boots.” “This is totally random Vanessa… why are you showing us this?”

“Look at the beautiful light. It gives them such dignity… like they are radiant.” “They make me think of the mess and the pain of life and that somehow all of it is held in beauty.” “They make me want to cry… look how carefully he has painted them.”

The Wink

In 2019 my life fell out of London and landed in East Sussex with a thud. I determined I was done with Christian culture and Christian communities. Bruise-ingly disillusioned, I was going to let myself admit that I had lost my faith and just get on with my weird life with my weird people and not do the God thing anymore. Life, however, had other plans. And within a year I was settled in a perfect art studio space, next to a kitchen garden, on land set aside as a Christian retreat centre.

There was no obligation for me to get involved in the community there, but a musician friend invited me to join them for a night of worship, and she was kind and sensitive so I said yes. I instantly knew that it was a mistake. I could only, with integrity, sing about 3 words of the hundreds that appeared on the screen over the space of 1.5 hours. And whilst most of those around me had their hands in the air with faces turned upwards, seemingly radiating joy, I was sitting on the floor against a wall in a dark corner, with my knees to my chest, weeping.

“I think I’ve lost You. And if I’ve lost You then none of the decisions I’ve made in the last twenty years make sense anymore. All I feel is pain.”

And I remember that, after saying the words above in my head, I stretched my arms out over my knees, turned my palms upwards, bent my head down, and said “help.”

And I was helped.

By a light-footed dancing figure that left the crowd and bent down to join me. My eyes were closed but I could sense their presence. See their movements. They took my upturned hands in theirs, pressed their thumbs on the centre of my palms, and looked directly at my face.

“I came to meet the pain of the world, Vanessa. You are learning to experience and stay with the pain. That’s where I am.”

It was Jesus.

And He seemed a little relieved to have a break from the leaping around-ness. And to be kneeling for a moment in the dark with me. Reminding me, by touching my own palms, of the wounds of His death. Fearless in His simple resolve that, rather than having lost Him, I was perhaps for the first time beginning to really know Him.

This was an exquisite insight, which had a gentle radiance that I hope will stay with me forever.

And then it happened.

This Jesus began to get up, with the intention of joining the happy people again. But, as I looked up, sad to see Him go, He turned and looked me direct in my now open eyes.

And He smiled.

And winked.

And moved on.

The Dignity of All Things

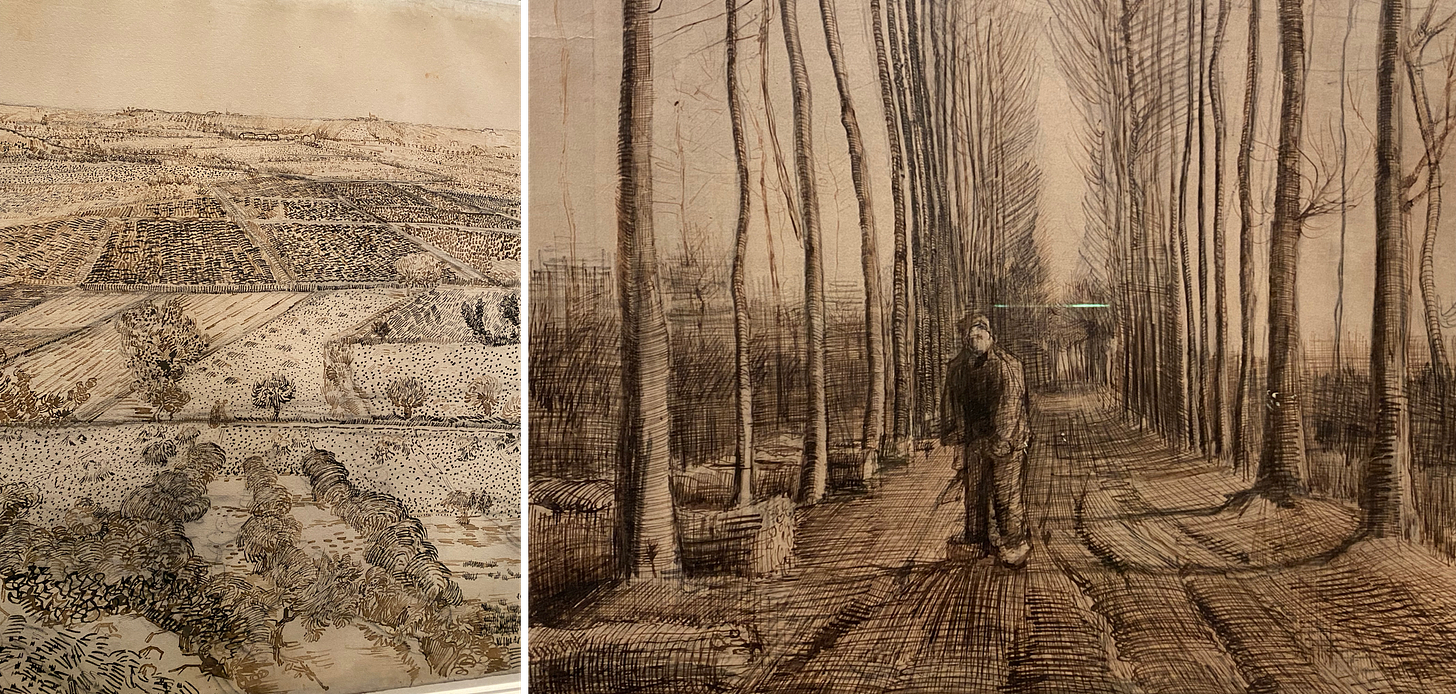

Fast forward to October 2025 and I am walking with great delight and curiosity through the small but perfectly formed Van Gogh/Anselm Kiefer exhibition at the Royal Academy in London. Kiefer is a big fan of Van Gogh’s and, though their work appears vastly different, was influenced by his palette, his sense of composition, his sensitivity to place and land, and his imbuing of every element of his drawings and paintings with poetry and meaning.

There were some sweet drawings in this show, but most of Kiefer’s work was vast. Expressive. Bombastic. Radiantly bleak. Evocative. Visceral. Messy. Monumental. In Venice a few years back I saw work that had been commissioned for a specific state room in the Doge’s Palace, and was told that one of his paintings was 70 ft high.

And there, in the midst of 3 epic land-dream-scapes, in the final room of the RA show, was Van Gogh’s little ‘wink’.

I wasn’t expecting it, so when I turned from admiring the expanse of Kiefer’s work to see the comparatively tiny black boots quietly radiating glory from the wall behind me, I gasped. Then burst out laughing.

It was hilarious. Here was Kiefer’s incredible mythically-earthy-existentially-heroic kind of exploration of the human condition and the pain we were projecting on to the natural world around us. And it was instantly upstaged by the simple economy of Van Gogh’s pair of worn black boots.

And when the bleakness of Kiefer’s landscapes encountered the radiance of Van Gogh’s boots… when those boots walked that land… the earth sang.

At that moment a random man came and stood next to me and said “when I go to Kiefer exhibitions I always take mushrooms.” He seemed pretty un-creepy, so I asked him why. “It’s how they want to be experienced. In an altered state. They want to take you elsewhere.” That made sense to me. But then I smiled and pointed to my beloved boots. “Those don’t need mushrooms. Go check them out.”

If it is true that Van Gogh killed himself, it had to be because there was too much meaning, rather than too little. Like Kiefer, his fields stretch for miles and take the viewers eye out and beyond. But Van Gogh’s fields are bursting with discreet life and variety. Lone, lame workers limp their way home through trees that sing with golden evening light. Weary poets sweat colour and beauty through their tired pores. Dying sunflowers burst with seeds.

When Van Gogh stayed in London, he drew those he saw suffering their way through everyday life around him. And each — in their torn clothes, faces etched with pain — is given a dignity so confronting that it is hard to look at them for long.

The Winking Gospel

And so I return to his boots. Quiet. Worn. Tired. Labouring under injustice and hunger. Overlooked. Battered. Ugly. Pained. Alone.

And then they wink at me. And the light around them pierces my soul. Makes me weep.

Van Gogh’s good news. All things are rooted in, and can therefore radiate, beauty. Humans fighting to survive holds dignity. Pain is and will be held in hands that care. All things can be, are being, and will be, redeemed. Salvation. Saved. We are saved by Beauty.

In my vision of the winking Jesus, I glimpsed an eye that danced with joy and endless vitality. It said to me: “I promise this (the pain of the world) is only a moment… you’ll see Vanessa… I promise it will make sense.”

That glimpse was enough for a life time. I believed it. And it began to recover my faith. Without me needing to move an inch. No leaping. No forcing. Just arms extended, palms open, and a tear-stained face in the dark.

The bleakness of the world judged, as with Johnny Cash’s ‘Man in Black’, by a shimmeringly mournful pair of black boots.

Before leaving the exhibition I turned to see Mr. Mushroom still leaning in to experience those boots. Allowing them to alter his state. Experiencing their Gospel of Dignity.

Perhaps I should take some of his mushrooms before joining the panel next weekend.

Vanessa Chamberlin is an artist, writer, spiritual director and practical theologian. You’ll find her writing at The Tuning Fork on Substack, and can read about her spiritual direction and hosting practices at rockdove.org.uk

If you enjoyed this topic in particular, here’s a piece where Vanessa dives a bit more into thoughts around Van Gogh’s work.

Quick response because I saw it on Passio… I absolutely get this, and had a similar experience at the VG museum in Amsterdam last year. I’ve read quite a bit recently from people who have had journeys away from the Church, then back to God. I’ve seen less from people raised without any organised faith but drawn to the sort of relationship with a divine you are talking about here. I also know that new belief can be deafening and dogmatic. Oh darn, I’ve done one of those ‘actually more of a statement…’ questions that everyone hates. Anyway, thanks for this.

You made me ask myself that question, “what is the gospel?” I think it’s the truth and if we all learned it and lived it, then everyone would know that they are loved. Van Gogh knew to look for the truth that needed to be painted.